The Conversation : "Fake papers are contaminating the world’s scientific literature, fueling a corrupt industry and slowing legitimate lifesaving medical research"

Over the past decade, furtive commercial entities around the world have industrialized the production, sale and dissemination of bogus scholarly research, undermining the literature that everyone from doctors to engineers rely on to make decisions about human lives.

It is exceedingly difficult to get a handle on exactly how big the problem is. Around 55,000 scholarly papers have been retracted to date, for a variety of reasons, but scientists and companies who screen the scientific literature for telltale signs of fraud estimate that there are many more fake papers circulating – possibly as many as several hundred thousand. This fake research can confound legitimate researchers who must wade through dense equations, evidence, images and methodologies only to find that they were made up.

Even when the bogus papers are spotted – usually by amateur sleuths on their own time – academic journals are often slow to retract the papers, allowing the articles to taint what many consider sacrosanct: the vast global library of scholarly work that introduces new ideas, reviews other research and discusses findings.

These fake papers are slowing down research that has helped millions of people with lifesaving medicine and therapies from cancer to COVID-19. Analysts’ data shows that fields related to cancer and medicine are particularly hard hit, while areas like philosophy and art are less affected. Some scientists have abandoned their life’s work because they cannot keep pace given the number of fake papers they must bat down.

The problem reflects a worldwide commodification of science. Universities, and their research funders, have long used regular publication in academic journals as requirements for promotions and job security, spawning the mantra “publish or perish.”

But now, fraudsters have infiltrated the academic publishing industry to prioritize profits over scholarship. Equipped with technological prowess, agility and vast networks of corrupt researchers, they are churning out papers on everything from obscure genes to artificial intelligence in medicine.

These papers are absorbed into the worldwide library of research faster than they can be weeded out. About 119,000 scholarly journal articles and conference papers are published globally every week, or more than 6 million a year. Publishers estimate that, at most journals, about 2% of the papers submitted – but not necessarily published – are likely fake, although this number can be much higher at some publications.

While no country is immune to this practice, it is particularly pronounced in emerging economies where resources to do bona fide science are limited – and where governments, eager to compete on a global scale, push particularly strong “publish or perish” incentives.

As a result, there is a bustling online underground economy for all things scholarly publishing. Authorship, citations, even academic journal editors, are up for sale. This fraud is so prevalent that it has its own name: paper mills, a phrase that harks back to “term-paper mills,” where students cheat by getting someone else to write a class paper for them.

The impact on publishers is profound. In high-profile cases, fake articles can hurt a journal’s bottom line. Important scientific indexes – databases of academic publications that many researchers rely on to do their work – may delist journals that publish too many compromised papers. There is growing criticism that legitimate publishers could do more to track and blacklist journals and authors who regularly publish fake papers that are sometimes little more than artificial intelligence-generated phrases strung together.

To better understand the scope, ramifications and potential solutions of this metastasizing assault on science, we – a contributing editor at Retraction Watch, a website that reports on retractions of scientific papers and related topics, and two computer scientists at France’s Université Toulouse III–Paul Sabatier and Université Grenoble Alpes who specialize in detecting bogus publications – spent six months investigating paper mills.

This included, by some of us at different times, trawling websites and social media posts, interviewing publishers, editors, research-integrity experts, scientists, doctors, sociologists and scientific sleuths engaged in the Sisyphean task of cleaning up the literature. It also involved, by some of us, screening scientific articles looking for signs of fakery.

Problematic Paper Screener: Trawling for fraud in the scientific literature

What emerged is a deep-rooted crisis that has many researchers and policymakers calling for a new way for universities and many governments to evaluate and reward academics and health professionals across the globe.

Just as highly biased websites dressed up to look like objective reporting are gnawing away at evidence-based journalism and threatening elections, fake science is grinding down the knowledge base on which modern society rests.

As part of our work detecting these bogus publications, co-author Guillaume Cabanac developed the Problematic Paper Screener, which filters 130 million new and old scholarly papers every week looking for nine types of clues that a paper might be fake or contain errors. A key clue is a tortured phrase – an awkward wording generated by software that replaces common scientific terms with synonyms to avoid direct plagiarism from a legitimate paper.

Problematic Paper Screener: Trawling for fraud in the scientific literature

An obscure molecule

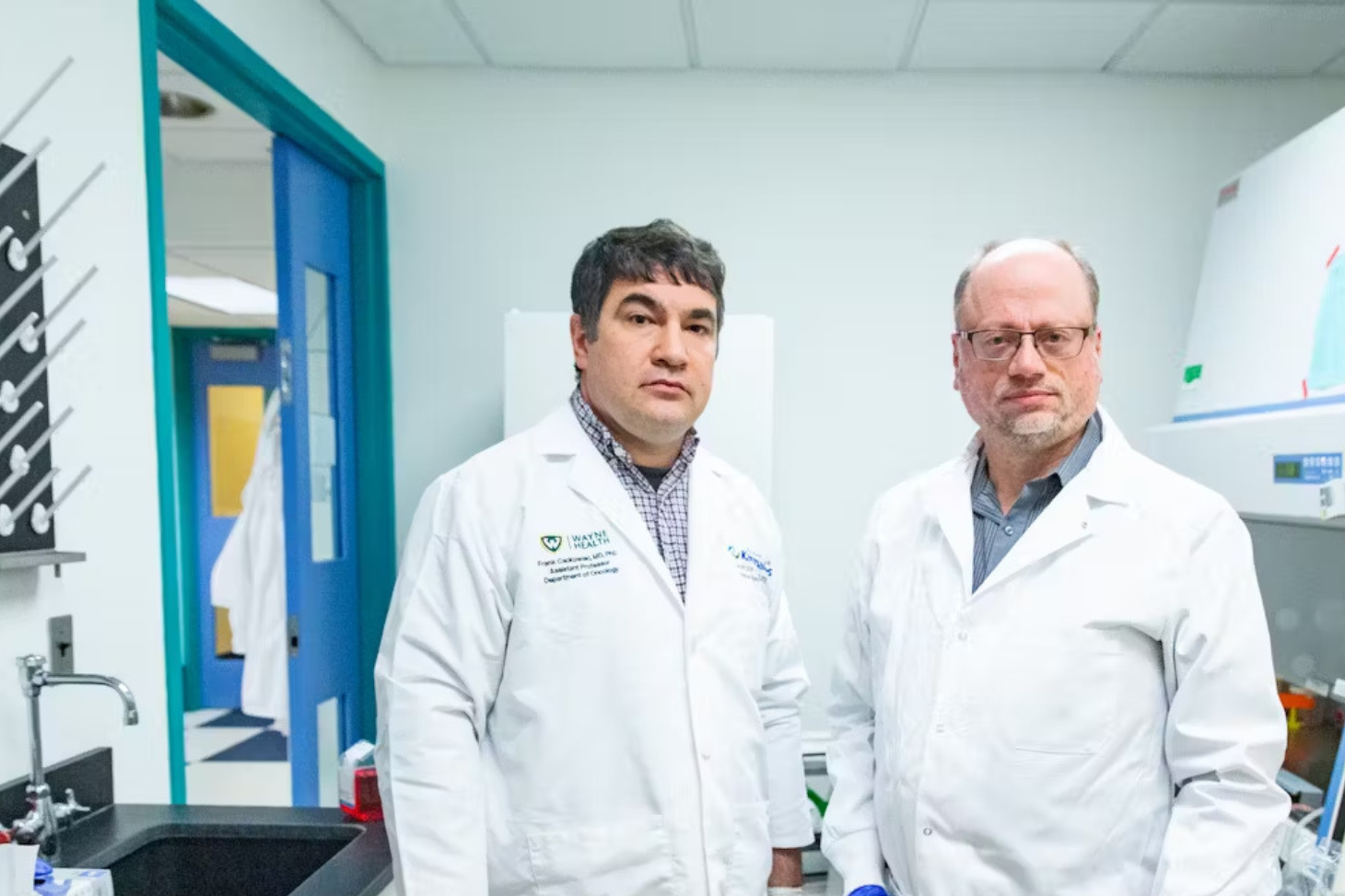

Frank Cackowski at Detroit’s Wayne State University was confused.

The oncologist was studying a sequence of chemical reactions in cells to see if they could be a target for drugs against prostate cancer. A paper from 2018 in the American Journal of Cancer Research piqued his interest when he read that a little-known molecule called SNHG1 might interact with the chemical reactions he was exploring. He and fellow Wayne State researcher Steven Zielske began a series of experiments to learn more about the link. Surprisingly, they found there wasn’t a link.

Meanwhile, Zielske had grown suspicious of the paper. Two graphs showing results for different cell lines were identical, he noticed, which “would be like pouring water into two glasses with your eyes closed and the levels coming out exactly the same.” Another graph and a table in the article also inexplicably contained identical data.

Zielske described his misgivings in an anonymous post in 2020 at PubPeer, an online forum where many scientists report potential research misconduct, and also contacted the journal’s editor. Shortly thereafter, the journal pulled the paper, citing “falsified materials and/or data.”

“Science is hard enough as it is if people are actually being genuine and trying to do real work,” says Cackowski, who also works at the Karmanos Cancer Institute in Michigan. “And it’s just really frustrating to waste your time based on somebody’s fraudulent publications.”

He worries that the bogus publications are slowing down “legitimate research that down the road is going to impact patient care and drug development.”

The two researchers eventually found that SNHG1 did appear to play a part in prostate cancer, though not in the way the suspect paper suggested. But it was a tough topic to study. Zielske combed through all the studies on SNHG1 and cancer – some 150 papers, nearly all from Chinese hospitals – and concluded that “a majority” of them looked fake. Some reported using experimental reagents known as primers that were “just gibberish,” for instance, or targeted a different gene than what the study said, according to Zielske. He contacted several of the journals, he said, but received little response. “I just stopped following up.”

The many questionable articles also made it harder to get funding, Zielske said. The first time he submitted a grant application to study SNHG1, it was rejected, with one reviewer saying “the field was crowded,” Zielske recalled. The following year, he explained in his application how most of the literature likely came from paper mills. He got the grant.

Today, Zielske said, he approaches new research differently than he used to: “You can’t just read an abstract and have any faith in it. I kind of assume everything’s wrong.”

Legitimate academic journals evaluate papers before they are published by having other researchers in the field carefully read them over. This peer review process is designed to stop flawed research from being disseminated, but is far from perfect.

Reviewers volunteer their time, typically assume research is real and so don’t look for signs of fraud. And some publishers may try to pick reviewers they deem more likely to accept papers, because rejecting a manuscript can mean losing out on thousands of dollars in publication fees.

“Even good, honest reviewers have become apathetic” because of “the volume of poor research coming through the system,” said Adam Day, who directs Clear Skies, a company in London that develops data-based methods to help spot falsified papers and academic journals. “Any editor can recount seeing reports where it’s obvious the reviewer hasn’t read the paper.”

With AI, they don’t have to: New research shows that many reviews are now written by ChatGPT and similar tools.

To expedite the publication of one another’s work, some corrupt scientists form peer review rings. Paper mills may even create fake peer reviewers impersonating real scientists to ensure their manuscripts make it through to publication. Others bribe editors or plant agents on journal editorial boards.

María de los Ángeles Oviedo-García, a professor of marketing at the University of Seville in Spain, spends her spare time hunting for suspect peer reviews from all areas of science, hundreds of which she has flagged on PubPeer. Some of these reviews are the length of a tweet, others ask authors to cite the reviewer’s work even if it has nothing to do with the science at hand, and many closely resemble other peer reviews for very different studies – evidence, in her eyes, of what she calls “review mills.”

“One of the demanding fights for me is to keep faith in science,” says Oviedo-García, who tells her students to look up papers on PubPeer before relying on them too heavily. Her research has been slowed down, she adds, because she now feels compelled to look for peer review reports for studies she uses in her work. Often there aren’t any, because “very few journals publish those review reports,” Oviedo-García says.

An ‘absolutely huge’ problem

It is unclear when paper mills began to operate at scale. The earliest article retracted due to suspected involvement of such agencies was published in 2004, according to the Retraction Watch Database, which contains details about tens of thousands of retractions. (The database is operated by The Center for Scientific Integrity, the parent nonprofit of Retraction Watch.) Nor is it clear exactly how many low-quality, plagiarized or made-up articles paper mills have spawned.

But the number is likely to be significant and growing, experts say. One Russia-linked paper mill in Latvia, for instance, claims on its website to have published “more than 12,650 articles” since 2012.

An analysis of 53,000 papers submitted to six publishers – but not necessarily published – found the proportion of suspect papers ranged from 2% to 46% across journals. And the American publisher Wiley, which has retracted more than 11,300 compromised articles and closed 19 heavily affected journals in its erstwhile Hindawi division, recently said its new paper-mill detection tool flags up to 1 in 7 submissions.

Day, of Clear Skies, estimates that as many as 2% of the several million scientific works published in 2022 were milled. Some fields are more problematic than others. The number is closer to 3% in biology and medicine, and in some subfields, like cancer, it may be much larger, according to Day. Despite increased awareness today, “I do not see any significant change in the trend,” he said. With improved methods of detection, “any estimate I put out now will be higher.”

The paper-mill problem is “absolutely huge,” said Sabina Alam, director of Publishing Ethics and Integrity at Taylor & Francis, a major academic publisher. In 2019, none of the 175 ethics cases that editors escalated to her team was about paper mills, Alam said. Ethics cases include submissions and already published papers. In 2023, “we had almost 4,000 cases,” she said. “And half of those were paper mills.”

Jennifer Byrne, an Australian scientist who now heads up a research group to improve the reliability of medical research, submitted testimony for a hearing of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Science, Space, and Technology in July 2022. She noted that 700, or nearly 6%, of 12,000 cancer research papers screened had errors that could signal paper mill involvement. Byrne shuttered her cancer research lab in 2017 because the genes she had spent two decades researching and writing about became the target of an enormous number of fake papers. A rogue scientist fudging data is one thing, she said, but a paper mill could churn out dozens of fake studies in the time it took her team to publish a single legitimate one.

“The threat of paper mills to scientific publishing and integrity has no parallel over my 30-year scientific career …. In the field of human gene science alone, the number of potentially fraudulent articles could exceed 100,000 original papers,” she wrote to lawmakers, adding, “This estimate may seem shocking but is likely to be conservative.”

In one area of genetics research – the study of noncoding RNA in different types of cancer – “We’re talking about more than 50% of papers published are from mills,” Byrne said. “It’s like swimming in garbage.”

In 2022, Byrne and colleagues, including two of us, found that suspect genetics research, despite not having an immediate impact on patient care, still informs the work of other scientists, including those running clinical trials. Publishers, however, are often slow to retract tainted papers, even when alerted to obvious signs of fraud. We found that 97% of the 712 problematic genetics research articles we identified remained uncorrected within the literature.

When retractions do happen, it is often thanks to the efforts of a small international community of amateur sleuths like Oviedo-García and those who post on PubPeer.

Jillian Goldfarb, an associate professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at Cornell University and a former editor of the Elsevier journal Fuel, laments the publisher’s handling of the threat from paper mills.

“I was assessing upwards of 50 papers every day,” she said in an email interview. While she had technology to detect plagiarism, duplicate submissions and suspicious author changes, it was not enough. “It’s unreasonable to think that an editor – for whom this is not usually their full-time job – can catch these things reading 50 papers at a time. The time crunch, plus pressure from publishers to increase submission rates and citations and decrease review time, puts editors in an impossible situation.”

In October 2023, Goldfarb resigned from her position as editor of Fuel. In a LinkedIn post about her decision, she cited the company’s failure to move on dozens of potential paper-mill articles she had flagged; its hiring of a principal editor who reportedly “engaged in paper and citation milling”; and its proposal of candidates for editorial positions “with longer PubPeer profiles and more retractions than most people have articles on their CVs, and whose names appear as authors on papers-for-sale websites.”

“This tells me, our community, and the public, that they value article quantity and profit over science,” Goldfarb wrote.

In response to questions about Goldfarb’s resignation, an Elsevier spokesperson told The Conversation that it “takes all claims about research misconduct in our journals very seriously” and is investigating Goldfarb’s claims. The spokesperson added that Fuel’s editorial team has “been working to make other changes to the journal to benefit authors and readers.”

Updated on January 31, 2025

Authors

Contributing editor

Retraction Watch

Cyril Labbé

Professor of Computer Science

Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA)

Guillaume Cabanac

Professor of Computer Science

Institut de Recherche en Informatique de Toulouse